War Horse

Untold story of the million horses sent to front line in First World War

Horses and men in gas masks during tests to find the best protection against gas attacks

THEY shared a bond like no other amid the horrors of the First World War trenches.

The soldier holding the reins of his trusted steed; the terrified horse powerless to dodge the hail of bullets being fired from the German machine guns.

Nearly 900,000 British men died in France between 1914 and 1918, one in eight of those who went to war.

Of the million horses sent overseas to help with the war effort, only 62,000 returned home. This is the forgotten tragedy of the Great War – a conflict that pitched as many animals into the line of fire as it did humans.

For years few knew of the unimaginable suffering of the beasts transported across the Channel to the Western Front. The novel War Horse, by former children’s laureate Michael Morpurgo, sold millions and the play of the same name is a West End hit.

But not until now, with the release of Stephen Spielberg’s film War Horse will the true extent of the four-legged warriors’ sacrifice be known.

The story is also the subject of a powerful new book, War Horses, by historian Simon Butler.

It describes the impenetrable bond between master and horse. Even those belonging to higher ranks were not spared the horrors of the front line, as General Jack Seely acknowledged.

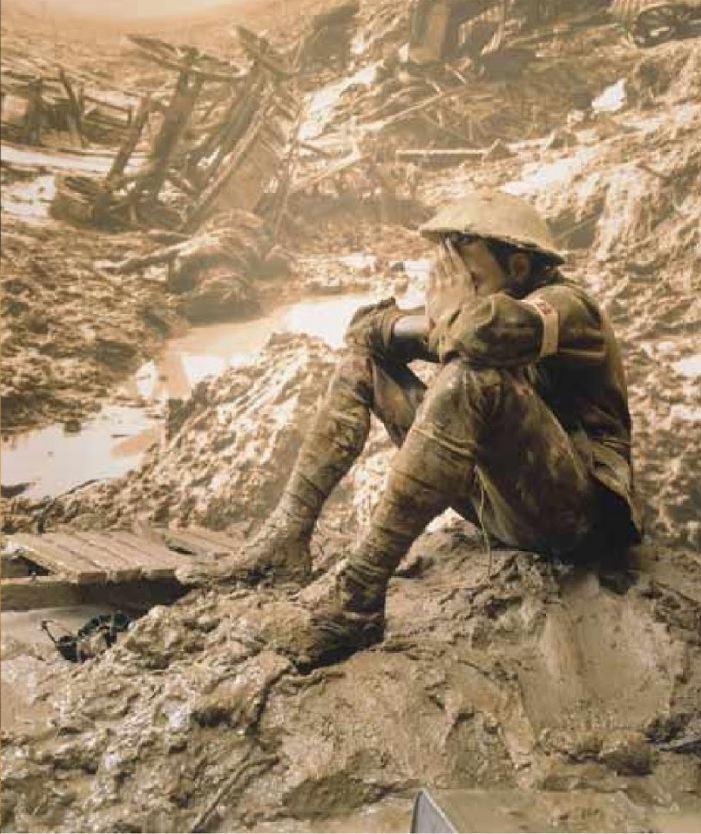

A soldier drives a horse and supply cart through water logged fields and roads

The general was famed for his heroics at the battle at Moreuil Wood where he led the charge on the back of his trusted horse Warrior.

General Seely said of his horse: “He had to endure everything most hateful to him – violent noise, the bursting of great shells and bright flashes at night, when the white light of bursting shells must have caused violent pain to such sensitive eyes as horses possess. Above all, the smell of blood, terrifying to every horse.

“Many people do not realise how acute is his sense of smell, but most will have read his terror when he smells blood.”

Poignant photos of horses with their masters bring home the horror endured by these most sensitive of creatures.

What is undeniable is the close relationship between horse and man, probably made tighter by the appalling bloodshed all around. For despite their strength, the horses were no less vulnerable to dangers of the battlefield.

“The sombre close of the Battle of the Somme was cruel to horses no less than men,” said General Seely.

“The roads were so completely broken up by alternate frost, snow and rain, that the only way to get ammunition to the forward batteries was to carry it up in panniers slung on horses. Often these poor beasts would sink deep into the mud.

“Sometimes, in spite of all their struggles, they could not extricate themselves, and died where they fell.”

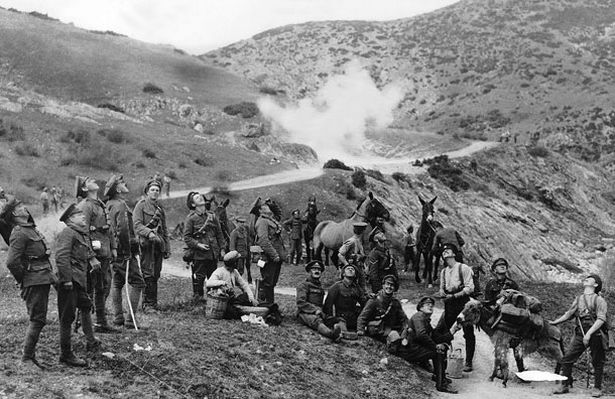

British soldiers standing on hillside with pack horses

Images show men of the Royal Scots Greys watering their animals next to a pond behind the front line. Troops are seen fitting special equine gas masks to ease the pain for their beloved animals. These stark shots tell a lot about the significance of horses in the bloodiest warfare in history.

A charity poster declaring Help the Horse to Save the Soldier showed how protecting the creatures was seen as being as important as looking after the men.

World War One was “the first and last global conflict in which the horse played a vital role”, Mr Butler explains.

The war horses shifted millions of tons of rations and ammunition’s up to the front line and also brought back the wounded on stretchers placed on carriages.

This meant they would be caught up in mustard gas attacks, get stuck on the barbed wire in front of the trenches and be left injured in no man’s land.

British troops attempt to rescue mules caught and trapped in a sea of mud

What comes across most of all is the sheer stupidity of sending horses into battle against howitzers and tanks.

In his diary, Lieutenant R G Dixon, of 14th Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery, remembered: “Heaving about in the filthy mud of the road was an unfortunate mule with both of his forelegs shot away. “The poor brute, suffering God knows what untold agonies and terrors, was trying desperately to get to its feet which weren’t there.

“Jerry’s shells were arriving pretty fast – we made some desperate attempts to get to the mule so that I could put a bullet behind its ear into the brain, but to no avail. The shelling got more intense – perhaps one would hit the poor thing and put it out of its misery.”

Mr Butler, who lives on Dartmoor where War Horse was filmed, said: “I was always interested in this subject, but I never realised how what happened to the horses was not properly documented before. My whole book is about the tragic story of how these ordinary horses were taken from farms by the military.

“For the men who served in the trenches it was a tragedy and for the people at home it was a tragedy too because they lost animals to which they had become attached.”

The sheer scale of the logistical operation to ferry the horses to France and then keep them fed and watered is unimaginable today. A nation which had depended on horsepower in farms and cities up until 1914 lost all its workhorses to the front and had to find mechanised alternatives. By 1918, there was no going back.

The book describes military “impressment squads” which descended on a village like the naval press gangs of yesteryear to round up all the horses.

One witness, Elizabeth Owen, recalled: “Everything in the village was done by horses. The khaki men tied them all together on a long rope, I think there were about 20 – all horses we used to know and love and feed.

“Then they started trotting them out of the village and as they went out of sight we were terribly sad.”

Michael Morpugo’s 1984 novel tells the story of a horse plucked from a farm through the people it meets in the war: a young Devon farmboy, a British cavalry officer, a German soldier, and an old Frenchman and his grand-daughter.

As the surviving shell-shocked soldiers trudged home after the 1918 Armistice, thoughts turned to the other innocent victims of the senseless loss of life – the horses.

Animal campaigners from the fledgling RSPCA campaigned to save the domesticated creatures now wandering aimlessly through the sodden landscape from French and German abattoirs.

Their intervention meant that at least a few lucky horses were able to return to their quiet stables in Norfolk, North Yorkshire and Devon to see out their final years.

Buy our purple poppy to donate and help horses in need today

Our purple poppy pin commemorates animals lost in conflicts around the world, available from our eBay for charity shop: Buy purple poppy Here 100% proceeds goes towards the care of horses at the Centre.